Italian American History

Indigenous - Exploration - America - Immigration - War - New Genesis - Leadership

American, Italian and Eurpean History and Culture all play an integral part toward understanding, celebrating, preserving Italian American Heritage. ITAA believes that "Italian American" history must be accurate, objective and fact based. To this end we provide the most comprehensive summary available of historical relevancy, as well have debunked fabrications by pseudo-historians, fraudulent opportunists and the politically misguided. We hope you enjoy your journey through history and use it as a tool for education but also to improve the future for generations to come. This account took (7) years to research and compile by ITAA and it begins appropriately with the 1'ST people to arrive and settle within what is called present-day America's, and then United States of America territories. The 1'ST were Eurasians between 15,000 - 30,000 BC, who became known as the indigenous peoples of the land, The Vikings in approximately 1,000 BC then arrived, followed by the Italians who started the "Age of Exploration". Italians discovered (for European leaders that is), mapped and explored the regions today called North, Central and South America. Other Europeans soon became enlightened about the proclaimed "New World" and competed for vast resources, which led to the colonization by European nations of these newly found, mysterious Western lands. The following depicts the history of America / Italian Americans including both contributions and challenges. ITAA's (8} Key Milestones of History describe America's origination, to its present-day, Below, first (7) with the 8'TH (1970-today) covered in our "Community" section for most recent/current life events.

30,000 BC-100 BC / Indigenous America - Ancestors Arrive From Eurasia Theory

It is not known exactly how or when natives first settled the present-dy Americas and the Theory has is that people migrated from Eurasia across Beringia, a "land bridge" that connected Siberia to present-day Alaska during the Last Glacial Period. Genetic evidence suggests at least 3 waves of migrants arrived from Asia, with the first between 15,000 - 30,000 years ago. These migrations continued to about 10,000 years ago, when the land bridge became submerged by the rising sea level at the onset of the current inter-glacial period. Numerous Paleoindian cultures occupied North America and genetic and linguistic data connect the Indigenous people of this continent with ancient northeast Asians. Archaeological and linguistic data has enabled scholars to discover some of the migrations within the Americas. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that pre-Clovis peoples settled in Texas some 16,000–20,000 years ago. Artifacts from the Clovis Culture were first excavated in 1932 near Clovis, New Mexico. The Clovis culture ranged over much of North America and appeared in South America and is identified by the distinctive Clovis point, a flaked flint spear-point with a notched flute, by which it was inserted into a shaft. The dating of Clovis materials has been by association with animal bones and by the use of carbon dating methods. Recent reexaminations of Clovis materials using improved carbon-dating methods produced results of 11,050 and 10,800 radiocarbon years (roughly 9100 to 8850 BCE). Numerous other cultures, tribes and languages date up to pre-Viking / pre-Columbus periods: Folsom Tradition between 9000 BCE and 8000 BCE. Na-Dené-speaking peoples starting around 8000 BCE, reaching the Pacific Northwest by 5000 BCE and were the earliest ancestors of the Athabascan-speaking peoples, including the present-day Navajo and Apache. Oshara Tradition people from around 5,440 BCE to 460 CE, part of the SW Archaic Tradition. Poverty Point culture is a Late Archaic archaeological culture that inhabited the area of the lower Mississippi Valley, surrounding Gulf Coast from 2200 BCE to 700 BCE, during the Late Archaic period. Historical sites and cultures include: Adena, Old Copper, Oasisamerica, Woodland, Fort Ancient, Hopewell tradition and Mississippian cultures. When combining all published estimates of populations throughout the Americas, we find a probable Indigenous population of 60 million in 1492. Europe's entire population at the time was 70 to 88 million spread over less than one half the area.

100 BC-1300 AD / Roman Empire / Vikings' Settlement - Indigenous Western Territory

27 BC – 476 AD - The Rise And Fall Of the Roman Empire: Founded when Augustus Caesar proclaimed himself the first emperor of Rome in 31 BC and came to an end with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 CE. Ancient Rome grew from a small town on the Tiber River into an empire that ruled much of the world including Europe, Britain, much of western Asia, northern Africa and the Mediterranean islands. After 450 years as a republic, Rome became an empire in the wake of Julius Caesar’s rise in the first century, Gaius Julius Caesar (12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general, statesman and member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating Pompey in a Civil War and governing the Roman Republic as a dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. then "Emporer" Augustus Ceasar began a golden age of peace and prosperity. The Fall Of The Roman Empire: 376–476 was the process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and enormous "Western" territories were lost / divided for a multitude of reasons, both internal and invading barbarians all contributed to the collapse. In 376, unmanageable numbers of Goths and other non-Roman people, fleeing from the Huns, entered the Empire. In 395, after winning two destructive civil wars, Theodosius I died, leaving a collapsing empire to his two incapable sons. Further barbarians crossed the Rhine and other frontiers and, were not exterminated, expelled or subjugated. The Roman Western armed forces diminished and by 476 Rome had minimal power over Western territories as barbarian kingdoms were established. In 476, Germanic barbarian king Odoacer deposed the last emperor of the Roman Empire in Italy, Romulus Augustulus, and the Senate sent the imperial insignia to the Eastern Roman Emperor Flavius Zeno. The Western Roman legitimacy lasted for centuries and its cultural influence remains today. The Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire of course was powerful and survived, remained for centuries an effective power of the Eastern Mediterranean. The period described as Late Antiquity emphasizes the cultural continuities all throughout and far beyond the political collapse of uncontrollable Western lands, Italians were leading and the rise of a far more advanced civilization.

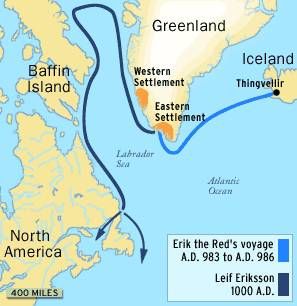

900-1100 AD (VIKINGS) In 1000 AD, an estimated 500 years before Christopher Columbus arrived to the “New World” as later labeled by Euopeans, “historic saga” had it that Viking explorer Leif Eriksson was the 1’ST European to land on the soil of North America and made a settlement but returned home after one winter season to succeed his father “Erik the Red” as Chief of the Greenland settlement. He never returned also because his brother Thorwald was killed by the indigenous people. Despite lack of documentation, it’s seems evident after various archaeological discoveries that Vikings had a presence in North America (settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Canada is well documented and accepted as historical fact by most scholars. Leif Erikson sailed to what he called "Vinland," now kown as Canadian province of "Newfoundland" but not the mainland known as the United States territories.

1300-1400 AD (SCOTTISH / ITALIAN) According to some scholars, Scottish Earl Sir Henry Sinclair of Orkney and Italian partner Nicolo Zeno landed in “North America” in 1397 because of a controversial map drawn by Zeno is thought to outline the coasts of Nova Scotia. Sinclair had routine contact with Viking lords, whose ancestors entered North America centuries before but no further evidence is provided either entered America. We have also found no Scottish or Italian historical record substantiating such voyages.

1400-1450 AD (CHINESE) The theory promoted by then retired British submariner Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book entitled "1421: the Year China Discovered America”, turns out to be pure fantasy according to experts from China, Europe and the United States. Menzies claims that Admiral Zheng reached the Americas 70 years before Christopher Columbus. The main reasoning, a stated copy of a 600-year-old map found in a used book shop, discovered by Beijing attorney Liu Gang, is purportedly an 18’TH century copy of a 1418 map charted by Chinese Admiral Zheng He, which shows the New World. Menzies has no formal training as a historian and his theories have been debunked by scholars. He claimed the Chinese have been sailing to the New World since 40,000 BC across the Pacific Ocean but provided no credible evidence. His other writings are just as fantastical. In 2008, University of London history professor Felipe Fernandez-Armesto stated his books are: 'the historical equivalent of stories about Elvis Presley in (the supermarket) and close encounters with alien hamsters. Felipe Fernández-Armesto further dismissed Menzies as "either a charlatan or a cretin". On 21 July 2004, PBS broadcast a two-hour-long documentary debunked all of Menzies's major claims, featuring professional Chinese historians. In 2004, historian Robert Finlay eviscerated Menzies in the Journal of World History for his "reckless manner of dealing with evidence" that led him to propose hypotheses "without a shred of proof". Finlay wrote: Unfortunately, this reckless manner of dealing with evidence is typical of 1421, vitiating all its extraordinary claims: the voyages it describes never took place, Chinese information never reached Prince Henry and Columbus, and there is no evidence of the Ming fleets in newly discovered lands. The fundamental assumption of the book—that the Yongle Emperor dispatched the Ming fleets because he had a "grand plan", a vision of charting the world and creating a maritime empire spanning the oceans—is simply asserted without a shred of proof. The reasoning of 1421 is inexorably circular, its evidence spurious, its research derisory, its borrowings unacknowledged, its citations slipshod, and its assertions preposterous. Examination of the book's central claims reveals they are uniformly without substance. A group of scholars and navigators—Su Ming Yang of the United States, Jin Guo-Ping and Malhão Pereira of Portugal, Philip Rivers of Malaysia, Geoff Wade of Singapore said of his book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, is a work of sheer fiction presented as revisionist history. Not a single document or artifact has been found to support his new claims on the supposed Ming naval expeditions beyond Africa. Menzies' numerous claims and the hundreds of pieces of "evidence" he has assembled have been thoroughly and entirely discredited by historians, maritime experts and oceanographers from China, the U.S., Europe and elsewhere. Academics have emphatically rejected all of this "evidence" as worthless and American history professor Ronald H. Fritze calls it the "almost cult-like" manner in which Menzies continues to drum up support for his hypothesis. A poll of History News Network ranks 1421 as the third-least credible history book ever printed and distributed. Menzies writings are considered fabrication.

1300-1600 AD / The Age Of Exploration - The Italian Renaissance Period Coincide

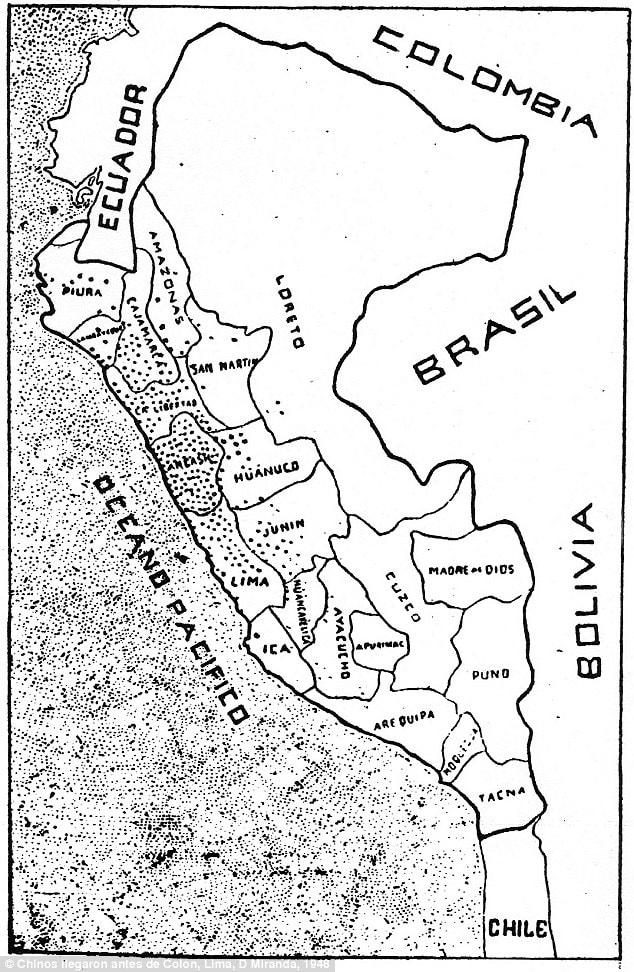

1300-1560 / ITALIANS: The Age of Exploration coincided with the Renaissance, approximately 1300 to 1600 which meticulously proven but exactl which Italian explorer arrived first is still circumspect. Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, Amerigo Vespucci led explorations (as) other Italians wee leading the Renaissance, making important contributions to humanity and influencing the awakening of improved fields of science, mathematics, philosophy, engineering, economics, international politics, law, medicine, literature, visual arts and music. In medieval Europe many of the first women scientists and physicians were Italian. On August 3, 1492, Italian navigator Christopher Columbus sailed from Palos, Spain, with 3 small ships, the Santa Maria, the Pinta and the Nina. On October 12, they reached the Bahamas, thinking it was East Asia. He claimed these lands for Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain, who sponsored his travels to find a western route to China, India, and Asian Islands. Columbus thought Cuba was China, and in December landed on Hispaniola, he thought may be Japan. He established a colony there with 39 men. Columbus determined by (1498–1500) that he was likely wrong and had not found India / East Asia. In 1493 he returned to Spain with “Indian” captives and was received with honors by Spain. John Cabot (Giulio Caboto) a Venetian explorer in 1497 voyaged to and stepped foot upon “North American”, soil where he claimed land in Canada for England. In May 1498 on a return voyage, he vanished. These were the 1’ST (2) Italians to explore and have presence in what is today known as the Bahamas, Canada, Cuba but there's no record that either made landing in the present-day United States then. On May 10, 1497, explorer Amerigo Vespucci also set out on his first of at least three voyages. On his third in 1499, historians recorded as his 3’RD expedition, he discovered present-day Rio de Janeiro and Rio de la Plata. Believing he discovered a new continent, he called “South America” the New World. But a letter dated in 1497 suggests that the 1499 voyage may have been Vespucci's 2’ND trip. The letter is written in Vespucci's pesona, but some historians dispute the authorship and the facts in it, claiming it a forgery. The letter to the Gonfalonier of Florence (a high official on the city-state's supreme executive council), accounts a 1497 expedition to the Bahamas and Central America. If the accounts of the letter are true, then Vespucci reached “mainland of Americas” a few months before John Cabot and a year before Columbus. In either event, by 1502, Vespucci said that Columbus was wrong, it was a “New World”. America was later named for Amerigo Vespucci in 1507. Exploration of the continent coincided with the Renaissance, with leadership / influences from so many famous Italian figures within world history such as: Galileo Galilei, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Alessandro Volta, Guglielmo Marconi, Maria Montessori, Maria Gaetana Agnesi, Giordano Bruno and the list is voluminous, of those who shaped and contributed to Western civilization and world.

1600-1800 Pietro Cesare Alberti Settles In America (aka New York) - U.S.A. Born

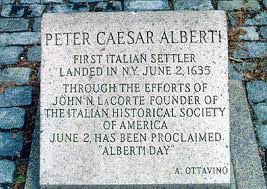

Giovanni da Verrazzano (in 1524) it was the Italian explorer, and 1’ST European to enter New York Harbor and the Hudson River. Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge in New York City is named for Giovanni da Verrazzano. In 1539 Marco da Nizza explored the territory that later became the states of Arizona and New Mexico. The first Italian to actually “reside” in America was Pietro Cesare Alberti, a Venetian seaman who, in 1635, settled in what would eventually become New York City. Several Italians explored and founded territotories throughout present-day U.S.A. including 1640, but most 1654 and 1663 what would become New York, New Jersey and the Lower Delaware River regions. Henri de Tonti (Enrico de Tonti) founded the first European settlement in Illinois in 1679, and in Arkansas in 1683 and co-founded New Orleans, and was governor of the Louisiana Territory for 20 years. His brother Alphonse de Tonty (Alfonso de Tonti) was co-founder of Detroit in 1701, and was its acting colonial Governor for 12 years. In 1519–25, Alessandro Geraldini was the first Catholic Bishop in the Americas, at Santo Domingo. Father François-Joseph Bressani (Francesco Giuseppe Bressani) arrived in the early 17th century. The southwest and California were explored and mapped by Italian Jesuit priest Eusebio Kino (Chino) in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The Taliaferro family from Venice, was one of the first families to settle in Virginia. François Marie, Chevalier de Reggio, an Italian nobleman came to Louisiana in 1751 where he held the title of Captain General of Louisiana until 1763. Another merchant, Francis Ferrari of Genoa, was naturalized as a citizen of Rhode Island in 1752. He died in 1753 and in his will speaks of Genoa, his ownership of three ships, cargo of wine and his wife Mary, who went on to own one of the oldest coffee houses in America, the Merchant Coffee House of New York on Wall Street at Water St. Her Merchant Coffee House moved across Wall Street in 1772. In 1773–85, Philip Mazzei, a physician and promoter of liberty, was a close friend and confidant of Thomas Jefferson. He published a pamphlet containing the phrase: "All men are by nature equally free and independent", which Jefferson incorporated essentially intact into the Declaration of Independence. Italian Americans served in the American Revolutionary War both as soldiers and officers. Francesco Vigo aided the colonial forces of George Rogers Clark during the American Revolutionary War by being one of the foremost financiers of the Revolution in the frontier Northwest. Later, he was a co-founder of Vincennes University in Indiana. After American independence numerous political refugees arrived, most notably: Giuseppe Avezzana, Alessandro Gavazzi, Silvio Pellico, Federico Confalonieri, and Eleuterio Felice Foresti. Giuseppe Garibaldi resided in the United States in 1850–51. At the invitation of Thomas Jefferson, Carlo Bellini became the first professor of modern languages at the College of William & Mary, in the years 1779–1803. In 1801, Philip Trajetta (Filippo Traetta) established the nation's first conservatory of music in Boston, where, in the first half of the century, organist Charles Nolcini and conductor Louis Ostinelli were also active. In 1805 Thomas Jefferson recruited a group of musicians from Sicily to form a military band, later to become the nucleus of the U.S. Marine Band. The musicians included the young Venerando Pulizzi, who became the first Italian director of the band, and served in this capacity from 1816 to 1827. Francesco Maria Scala, an Italian-born naturalized American citizen, was one of the most important and influential directors of the U. S. Marine Band, from 1855 to 1871. Joseph Lucchesi, the third Italian leader of the U. S. Marine Band, served from 1844 to 1846. The first opera house in the country opened in 1833 in New York through the efforts of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's former librettist, who had immigrated to America and had become the first professor of Italian at Columbia College in 1825. During this period Italian explorers continued to be active in the West. In 1789–91 Alessandro Malaspina mapped much of the west coast of the Americas, from Cape Horn to the Gulf of Alaska. In 1822–23 the headwater region of the Mississippi was explored by Giacomo Beltrami in the territory that was later to become Minnesota, which named a county in his honor. Joseph Rosati was named the first Catholic bishop of St. Louis in 1824. In 1830–64 Samuel Mazzuchelli, a missionary and expert in Indian languages, ministered to European colonists and Native Americans in Wisconsin and Iowa for 34 years and, after his death, was declared Venerable by the Catholic Church. Father Charles Constantine Pise, a Jesuit, served as Chaplain of the Senate from 1832 to 1833, the only Catholic priest ever chosen to serve in this capacity. Missionaries of the Jesuit and Franciscan orders were active in many parts of America. Italian Jesuits founded numerous missions, schools and two colleges in the west. Giovanni Nobili founded the Santa Clara College (now Santa Clara University) in 1851. The St. Ignatius Academy (now University of San Francisco) was established by Anthony Maraschi in 1855. The Italian Jesuits also laid the foundation for the wine-making industry that would later flourish in California. In the east, the Italian Franciscans founded hospitals, orphanages, schools, and the St. Bonaventure College (now St. Bonaventure University), established by Panfilo da Magliano in 1858. In 1837, John Phinizy (Finizzi) became the mayor of Augusta, Georgia. Samuel Wilds Trotti of South Carolina was the first Italian American to serve in the US Congress (a partial term, from December 17, 1842 to March 3, 1843). In 1849, Francesco, de Casale began publishing the Italian American newspaper "L'Eco d'Italia" in New York, the first of many to eventually follow. In 1848 Francis Ramacciotti, piano string inventor and manufacturer, immigrated to the U.S. from Tuscany. Review of the Garibaldi Guard by President Abraham Lincoln, approximately 7,000 Italian Americans served in the Civil War. While a smaller number served in the Confederate Army, such as General William B. Taliaferro (of English-American and Anglo-Italian descent), the great majority of Italian-Americans, for both demographic and ideological reasons, served in the Union Army (including generals Edward Ferrero and Francis B. Spinola). The Garibaldi Guard recruited volunteers for the Union Army from Italy and other European countries to form the 39th New York Infantry. Six Italian Americans received the Medal of Honor during the war, among whom was Colonel Luigi Palma di Cesnola, who later became the first Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York (1879-1904). Beginning in 1863, Italian immigrants were one of the principal groups, along with the Irish, that built the Transcontinental Railroad west from Omaha, Nebraska. In 1866 Constantino Brumidi completed the frescoed interior of the United States Capitol dome in Washington, and spent the rest of his life executing still other artworks to beautify the Capitol. The first Columbus Day celebration was organized by Italian Americans in San Francisco in 1869. The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum on Staten Island. An immigrant, Antonio Meucci, brought with him a concept for the telephone. He is credited by many researchers with being the first to demonstrate the principle of the telephone in a patent caveat he submitted to the U.S. Patent Office in 1871; however, considerable controversy existed relative to the priority of invention, with Alexander Graham Bell also being accorded this distinction. (In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution on Meucci (H.R. 269) declaring that "his work in the invention of the telephone should be acknowledged.") During this period, Italian Americans established a number of institutions of higher learning. Las Vegas College (now Regis University) was established by a group of exiled Italian Jesuits in 1877 in Las Vegas, New Mexico. The Jesuit Giuseppe Cataldo, founded Gonzaga College (now Gonzaga University) in Spokane, Washington in 1887. In 1886, Rabbi Sabato Morais, a Jewish Italian immigrant, was one of the founders and first president of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York. Also during this period, there was a growing presence of Italian Americans in higher education. Vincenzo Botta was a distinguished professor of Italian at New York University from 1856 to 1894 and Gaetano Lanza was a professor of mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for over 40 years, beginning in 1871. Italian Americans continued their involvement in politics. Anthony Ghio became the mayor of Texarkana, Texas in 1880. Francis B. Spinola, the 1'ST Italian American to serve a full term in Congress, elected in 1887, NY.

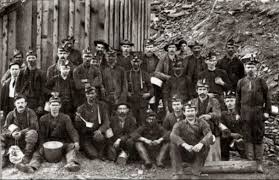

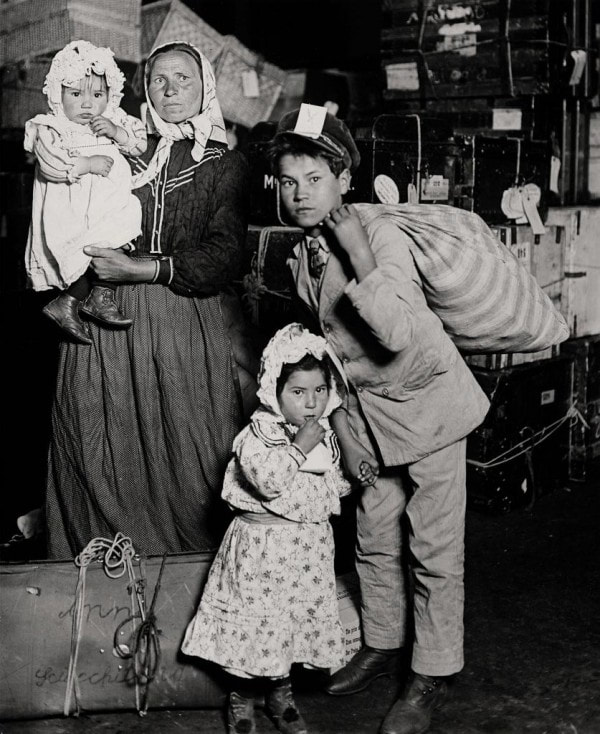

1880-1916's / The Great Arrival - 4 Million + Italians Migrate To Ellis Island, U.S.A.

Prior to 1870 less than 25,000 Italian Americans resided in the U.S. From 1880 to 1914, 13 million Italians migrated out of Italy, making Italy the scene of one of the largest voluntary emigration in recorded world history. During this period of mass migration, 4 million Italians arrived in the United States, 3 million of them between 1900 and 1914. Most planned to stay a few years, then take their earnings and return home. The immigrants often faced great challenges. Unskilled immigrants found employment primarily in low-wage manual-labor jobs and, if unable to find jobs on their own, turned to the padrone system whereby Italian middlemen (padroni) found jobs for groups of men and controlled their wages, transportation, and living conditions for a fee. According to historian Alfred T. Banfield: Criticized by many as slave traders who preyed upon poor, bewildered peasants, the 'padroni' often served as travel agents, with fees reimbursed from paychecks, as landlords who rented out shacks and boxcars, and as storekeepers who extended exorbitant credit to their Italian laborer clientele. Despite such abuse, not all 'padroni' were dastardly and most Italian immigrants reached out to their 'padroni' for economic salvation, considering them either as godsends or necessary evils. The Italians whom the 'padroni' brought to Maine generally had no intention of settling there, and most were sojourners who either returned to Italy or moved on to another job somewhere else. Nevertheless, thousands of Italians did settle in Maine, creating "Little Italies" in Portland, Millinocket, Rumford, and other towns where the 'padroni' remained as strong shaping forces in the new communities. In terms of the push-pull model of immigration, America provided the pull factor by the prospect of jobs that unskilled uneducated Italian peasant farmers could do. Peasant farmers accustomed to hard work in the Mezzogiorno, for example, took jobs building railroads and constructing buildings, while others took factory jobs that required little or no skill. The push factor came from Italian unification in 1861, which caused economic conditions to considerably worsen for many. Major factors that contributed to the large exodus from both northern and southern Italy after unification included political and social unrest, the government's allocation of much more of its resources to the industrialization of the North than to that of the South, an inequitable tax burden on the South, tariffs on the products of the South, soil exhaustion and erosion, and military conscription lasting seven years. The poor economic situation following unification became untenable for many sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and small business and land owners. Multitudes chose to emigrate rather than face the prospect of a deepening poverty. A large number of these were attracted to the U.S., which at the time was actively recruiting workers from Italy and elsewhere to fill the labor shortage that existed in the years following the Civil War. Often the father and older sons would go first, leaving the mother and the rest of the family behind until the male members could afford their passage. Many sought housing in the older sections of the large Northeastern cities where they settled, that became known as "Little Italies", frequently in overcrowded substandard tenements which were often dimly lit with poor heating and ventilation. Tuberculosis and other communicable diseases were a constant health threat for the immigrant families that were compelled by economic circumstances to live in these dwellings. Other immigrant families lived in single-family abodes, which was more typical in areas outside of the enclaves of the large Northeastern cities, and other parts of the country as well. An estimated 49 per cent of Italians who migrated to the Americas between 1905 (when return migration statistics began) and 1920 did not remain in the United States. These so-called "birds of passage", intended to stay in the United States for only a limited time, followed by a return to Italy with enough in savings to re-establish themselves there. While many did return to Italy, others chose to stay, or were prevented from returning by the outbreak of World War I. The Italian male immigrants in the Little Italies were most often employed in manual labor and were heavily involved in public works, such as the construction of roads, railway tracks, sewers, subways, bridges and the first skyscrapers in the northeastern cities. As early as 1890, it was estimated that around 90 percent of New York City's and 99% of Chicago's public works employees were Italians. The women most frequently worked as seamstresses in the garment industry or in their homes. Many established small businesses in the Little Italies to satisfy the day-to-day needs of fellow immigrants. A New York Times article from 1895 provides a glimpse into the status of Italian immigration at the turn of the century. The article states: Of the half million Italians that are in the United States, about 100,000 live in the city, and including those who live in Brooklyn, Jersey City, and the other suburbs the total number in the vicinity is estimated at about 160,000. After learning our ways they become good, industrious citizens. The New York Times in May 1896 sent its reporters to characterize the Little Italy/Mulberry neighborhood: They are laborers; toilers in all grades of manual work; they are artisans, they are junkmen, and here, too, dwell the rag pickers....There is a monster colony of Italians who might be termed the commercial or shop keeping community of the Latins. Here are all sorts of stores, pensions, groceries, fruit emporiums, tailors, shoemakers, wine merchants, importers, musical instrument makers. There are notaries, lawyers, doctors, apothecaries, undertakers. There are more bankers among the Italians than among any other foreigners except the Germans in the city. The masses of Italian immigrants that entered the United States (1890-1900) posed a change in the labor market, prompting Fr. Michael J. Henry to write a letter in October 1900 to the Bishop John J. Clency of Sligo, Ireland; warning: [that unskilled young Irishmen would have to enter into competition with their pick-axe and shovel against other nationalities - Italians, Poles etc. to eke out bare existence. The Italians are more economic, can live on poor fare and consequently can afford to work for less wages than the ordinary Irishman The Brooklyn Eagle in a 1900 article addressed the same reality: The day of the Irish hod-carrier has long been past ... But it is the Italian now that does the work. Then came the Italian carpenter and finally the mason and the bricklayer. In spite of the economic hardship of the immigrants, civil and social life flourished in the Italian American neighborhoods of the large Northeastern cities. Italian theater, band concerts, choral recitals, puppet shows, mutual-aid societies, and social clubs were available to the immigrants. An important event, the "festa", became for many an important connection to the traditions of their ancestral villages in Italy. The festa involved an elaborate procession through the streets in honor of a patron saint or the Virgin Mary in which a large statue was carried by a team of men, with musicians marching behind. Followed by food, fireworks and general merriment, the festa became an important occasion that helped give the immigrants a sense of unity and common identity. An American teacher who had studied in Italy, Sarah Wool Moore was so concerned with grifters luring immigrants into rooming houses or employment contracts in which the bosses got kickbacks that she pressed for the founding of the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants (often called the Society for Italian Immigrants). The Society published lists of approved living quarters and employers. Later, the organization began establishing schools in work camps to help adult immigrants learn English. Wool and the Society began organizing schools in the labor camps which employed Italian workers on various dam and quarry projects in Pennsylvania and New York. The schools focused on teaching phrases that workers needed in their everyday tasks. Because of the Society's success in helping immigrants, they received a commendation from the Commissioner of Emigration for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1907. The destinations of many of the Italian immigrants were not only the large cities of the East Coast, but also more remote regions of the country, such as Florida and California. They were drawn there by opportunities in agriculture, fishing, mining, railroad construction, lumbering and other activities underway at the time. Oftentimes, the immigrants contracted to work in these areas of the country as a condition for payment of their passage. It was not uncommon, especially in the South, for the immigrants to be subjected to economic exploitation, hostility and sometimes even violence. The Italian laborers who went to these areas were in many cases later joined by wives and children, which resulted in the establishment of permanent Italian American settlements in diverse parts of the country. A number of towns, such as Roseto, Pennsylvania. Tontitown, Arkansas, and Valdese, North Carolina were founded by Italian immigrants during this era. A number of major business ventures were founded by Italian Americans which added to the discrimination and jealously of Italian immigrants, especially in rural areas and the South predominately. The March 14, 1891, New Orleans lynchings were the murders of 11 Italian Americans in New Orleans, Louisiana, by a mob for their alleged role in the murder of city police chief David Hennessy after some of them had been acquitted at trial. It was one of the largest single mass lynchings in American history. The lynching took place the day after the trial of nine of the nineteen men indicted in Hennessy's murder. Six of these defendants were acquitted, and a mistrial was declared for the remaining three because the jury failed to agree on their verdicts. There was widespread suspicion in the city that an Italian network of criminals was responsible for the killing of the police chief, in a period of anti-Italian sentiment and rising crime. Believing the jury had been bribed, a mob broke into the jail where the men were being held and killed eleven of the prisoners, most by shooting. The mob outside the jail numbered in the thousands and included some of the city's most prominent citizens. American press coverage of the event was largely congratulatory, and those responsible for the lynching were never charged. The incident had serious national repercussions. The Italian consul Pasquale Corte in New Orleans registered a protest and left the city in May 1891 at his government's direction. The New York Times published his lengthy statement charging city politicians with responsibility for the lynching of the Italians. Italy cut off diplomatic relations with the United States, sparking rumors of war. Increased anti-Italian sentiment led to calls for restrictions on immigration. In late 19th-century America, there was a growing prejudice against Italians, who had entered to fill the demand for more labor. They were immigrating to the American South, particularly Florida and Louisiana, in large numbers because of poor conditions at home and to fill the shortage of labor created by the end of slavery and the preference of freedmen to work on their own accounts as sharecroppers. Sugar planters, in particular, sought workers who were more compliant than former slaves; they hired immigrant recruiters to bring Italians to southern Louisiana. In the 1890s, thousands of Italians were arriving in New Orleans each year. Many settled in the French Quarter, which by the early 20'TH century became known as "Little Sicily." The word "Mafia" had started to be used and awareness of the Italian Mafioso became established in the imagination of Americans. Throughout the country, those with strong, proud Italian heritage refused to be intimidated, oppressed or further harmed by such bigoted, discriminating and violent communities as witnessed within New Orleans. In fact, some of the initial financial support and physical "protection" for this wave of Italian immigrants against the institutionalized racism, abuses / discrimination and violence by White-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant (WASP)s and others, was manifested by the "Mafia".

1900-1940 / The "Genesis" Political, Social, Business & Entertainment Leadership

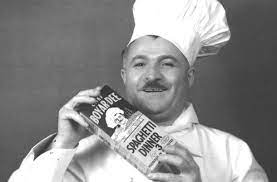

Amadeo Giannini originated the concept of branch banking to serve the Italian American community in San Francisco and most notably supported and promoted America's lower and middle-class instead of only America's wealthy so-called elite . He founded the Bank of Italy, which later became the Bank of America and also Trasamerica. His bank also provided the financing to the film industry developing on the West Coast at the time, including that for Walt Disney's Snow White, the first full-length animated motion picture to be made in the U.S. Other companies founded by Italian Americans – such as Ghirardelli Chocolate, Barnes & Noble, Company, Progresso, Planters Peanuts, Contadina, Chef Boyardee, Italian Swiss Colony wines and Jacuzzi – became nationally known brand names in time. An Italian immigrant, Italo Marciony (Marcioni), is credited with inventing the earliest version of an ice cream cone in 1898. Another Italian immigrant, Giuseppe Bellanca, brought with him in 1912 an advanced aircraft design, which he began producing. It was Charles Lindbergh's first choice for his flight across the Atlantic, but other factors ruled this out; however, one of Bellanca's planes, piloted by Cesare Sabelli and George Pond, made one of the first non-stop trans-Atlantic flights in 1934. A number of Italian immigrant families, including Grucci, Zambelli and Vitale, brought with them expertise in fireworks displays, and their pre-eminence in this field has continued to the present day. Following in the footsteps of Constantino Brumidi, other Italians and their descendants helped create Washington's impressive monuments. An Italian immigrant, Attilio Piccirilli, and his five brothers carved the Lincoln Memorial, which they began in 1911 and completed in 1922. Italian construction workers helped build Washington's Union Station, considered one of the most beautiful in the country, which was begun in 1905 and completed in 1908. The six statues that decorate the station's facade were sculpted by Andrew Bernasconi between 1909 and 1911. Two Italian American master stone carvers, Roger Morigi and Vincent Palumbo, spent decades creating the sculptural works that embellish Washington National Cathedral. Joe Petrosino in 1909. Italian conductors contributed to the early success of the Metropolitan Opera of New York (founded in 1880), but it was the arrival of impresario Giulio Gatti-Casazza in 1908, who brought with him conductor Arturo Toscanini, that made the Met an internationally known musical organization. Many Italian operatic singers and conductors were invited to perform for American audiences, most notably, tenor Enrico Caruso. The premiere of the opera La Fanciulla del West on December 10, 1910, with conductor Toscanini and tenor Caruso, and with the composer Giacomo Puccini in attendance, was a major international success as well as an historic event for the entire Italian American community. Francesco Fanciulli (1853-1915) succeeded John Philip Sousa as the director of United States Marine Band, serving in this capacity from 1892 to 1897. Italian Americans became involved in entertainment and sports. Rudolph Valentino was one of the first great film icons. Dixieland jazz music had a number of important Italian American innovators, the most famous being Nick LaRocca of New Orleans, whose quintet made the first jazz recording in 1917. The first Italian American professional baseball player, Ping Bodie (Francesco Pizzoli), began playing for the Chicago White Sox in 1912. Ralph DePalma won the Indianapolis 500 in 1915. Italian Americans became increasingly involved in politics, government and the labor movement. Andrew Longino was elected Governor of Mississippi in 1900. Charles Bonaparte was Secretary of the Navy and later Attorney General in the Theodore Roosevelt administration, and founded the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Joe Petrosino was a leading (NYPD) officer. Salvatore A. Cotillo was the first Italian-American to serve in both houses of the New York State Legislature and the first who served as Justice of the New York State Supreme Court. Fiorello LaGuardia was elected from New York in 1916 to US Congress. Numerous Italian Americans were at the forefront in fighting for worker's rights in industries such as mining, textiles and garment industries, most notable were Arturo Giovannitti, Carlo Tresca and Joseph Ettor. This period of remarkle leadership/progress couldn't be overshadowed by the two world wars that ensued.

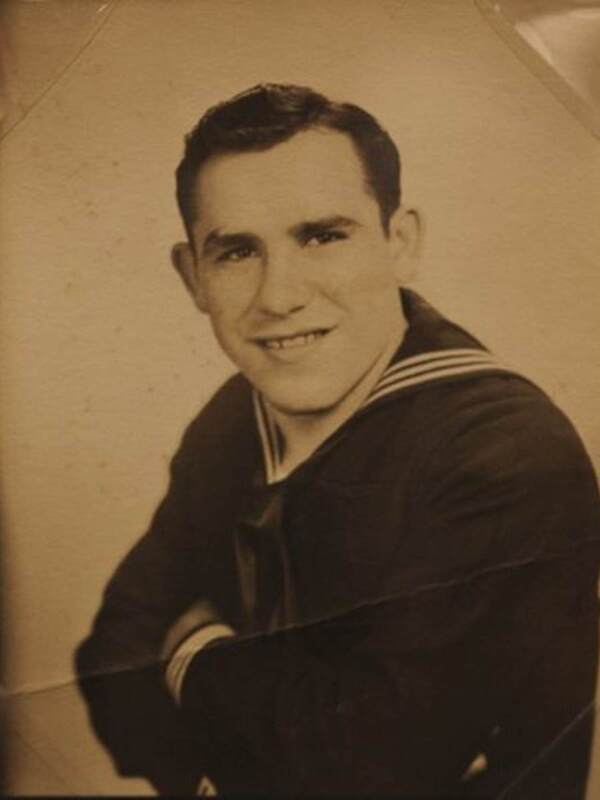

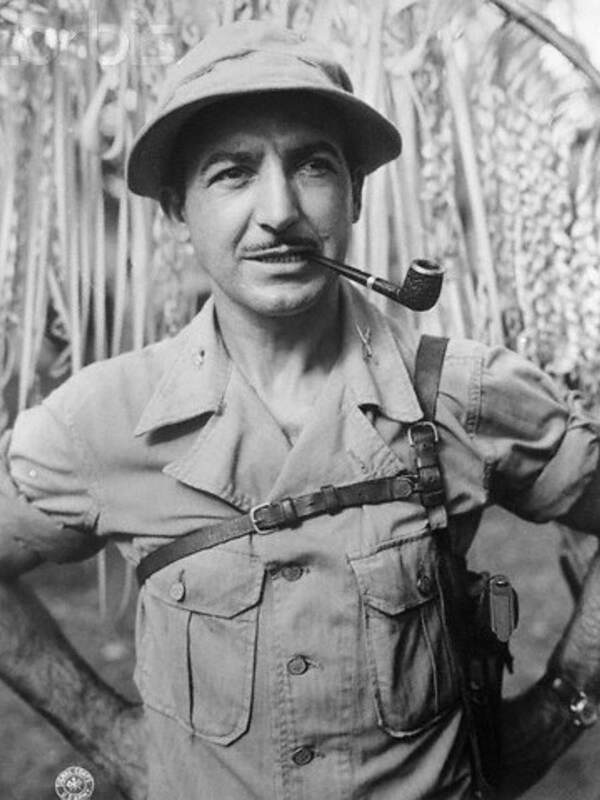

1917-1945 World War I & II Period: Additional Major Contributions / Challenges

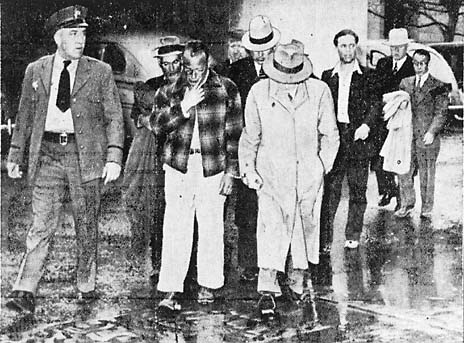

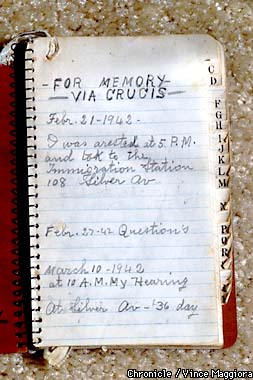

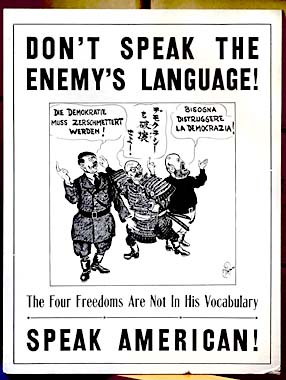

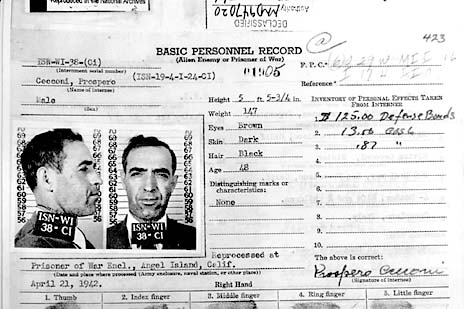

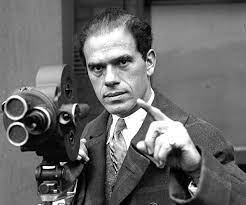

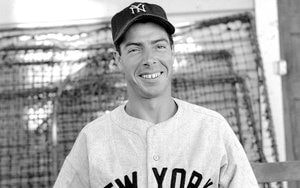

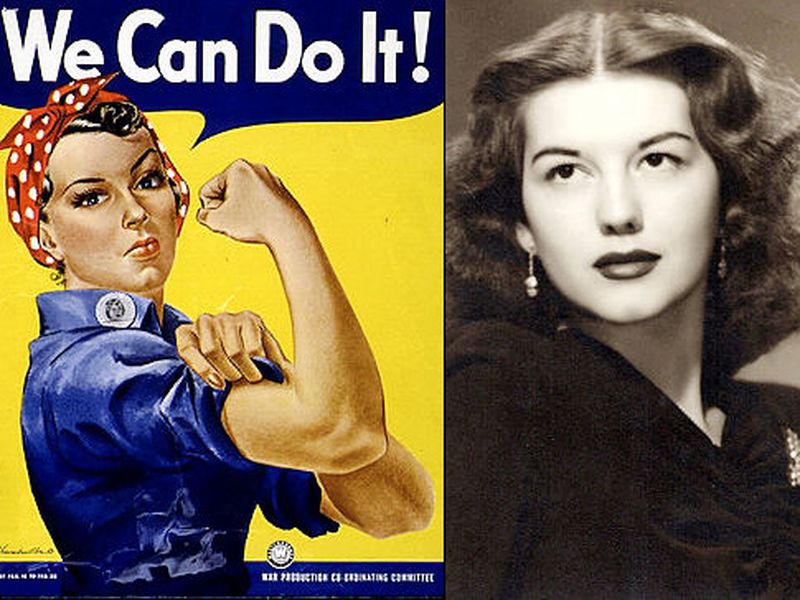

The United States entered World War I in 1917. The Italian American community strongly supported the war effort and its young men enlisted in large numbers in the American military. During the two years of the war (1917–18), Italian-Americans made up approximately 12% of the total American forces, a disproportionately high percentage of the total. An Italian-born American infantryman, Michael Valente, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his service. Another 103 Italian Americans (83 Italian born) were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest decoration. The war, together with the restrictive Emergency Quota Act of 1921, Immigration Act of 1924 and the implementation of the discriminatory National Origins Formula heavily curtailed Italian immigration. The quota allocated for Italians was 1/13 of that allocated for Germans and, in general, Anglo-Saxon and Northern European immigration was heavily favored. Despite implementation of the quota, the inflow of Italian immigrants remained between 6 or 7% of all immigrants. Fiorello La Guardia with Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938. Italian American WPA workers doing roadwork in Dorchester, Boston, 1930s. Rudolph Valentino with Alice Terry in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1921. Historical advertisement of an Italian American restaurant, between circa 1930 and 1945. In the interwar period, jobs as policemen, firemen and civil servants became increasingly available to Italian Americans; while others found employment as plumbers, electricians, mechanics and carpenters. Women found jobs as civil servants, secretaries, dressmakers, and clerks. With better paying jobs they moved to more affluent neighborhoods outside of the Italian enclaves. The Great Depression (1929–1939) had a major impact on the Italian American community, and temporarily reversed some of the earlier gains made. Many unemployed men (and a few women) found jobs on President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal work programs, such as the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corp. By 1920, numerous Little Italies had stabilized and grown considerably more prosperous as workers were able to obtain higher-paying jobs, often in skilled trades. In the 1920s and 1930s Italian Americans contributed significantly to American life and culte, politics, music, film, the arts, sports, the labor movement and business. In politics, Al Smith (Anglicized form of the Italian surname Ferraro) became the first governor of New York of Italian ancestry in 1920 —although the media characterized him as an Irish Catholic, he was of Italian / German decent. He was the first Catholic to receive a major party presidential nomination, as Democratic candidate for president in 1928. Angelo Rossi was mayor of San Francisco in 1931–1944. In 1933–34 Ferdinand Pecora led a Senate investigation of the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which exposed major financial abuses, and spurred Congress to rein in the banking industry. Liberal leader Fiorello La Guardia served as Republican and Fusion mayor of New York City in 1934–1945. On the far left Vito Marcantonio was first elected to Congress in 1934 from New York. Robert Maestri was mayor of New Orleans in 1936–1946. The Metropolitan Opera continued to flourish under the leadership of Giulio Gatti-Casazza, whose tenure continued until 1935. Rosa Ponselle and Dusolina Giannini, daughters of Italian immigrants, performed regularly at the Metropolitan Opera and became internationally known. Arturo Toscanini returned in the United States as the main conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1926–1936) and introduced many Americans to classical music through his NBC Symphony Orchestra radio broadcasts (1937–54). Ruggiero Ricci, a child prodigy born of Italian immigrant parents, gave his first public performance in 1928 at the age of 10, and had a long international career as a concert violinist. Popular singers of the period included Russ Columbo, who established a new singing style that influenced Frank Sinatra and other singers that followed. On Broadway, Harry Warren (Salvatore Guaragna) wrote the music for 42nd Street, and received three Academy Awards for his compositions. Other Italian American musicians and performers, such as Jimmy Durante, who later achieved fame in movies and television, were active in vaudeville. Guy Lombardo formed a popular dance band, which played annually on New Year's Eve in New York City's Times Square. The film industry of this era included Frank Capra, who received three Academy Awards for directing and Frank Borzage, who received two Academy Awards for directing. Italian American cartoonists were responsible for some of the most popular animated characters: Donald Duck was created by Al Taliaferro, Woody Woodpecker was a creation of Walter Lantz (Lanza), Casper the Friendly Ghost was co-created by Joseph Oriolo, and Tom and Jerry was co-created by Joseph Barbera. The voice of Snow White was provided by Adriana Caselotti, a 21-year-old soprano. In public art, Luigi Del Bianco was the chief stone carver at Mount Rushmore from 1933 to 1940. Simon Rodia, an immigrant construction worker, built the Watts Towers over a period of 33 years, from 1921 to 1954. In sports, Gene Sarazen (Eugenio Saraceni) won both the Professional Golf Association and U.S. Open Tournaments in 1922. Pete DePaolo won the Indianapolis 500 in 1925. Tony Lazzeri and Frank Crosetti started playing for the New York Yankees in 1926. Tony Canzoneri won the lightweight boxing championship in 1930. Lou Little (Luigi Piccolo) began coaching the Columbia University football team in 1930. Joe DiMaggio, who was destined to become one of the most famous players in baseball history, began playing for the New York Yankees in 1936. Hank Luisetti was a three time All-American basketball player at Stanford University from 1936 to 1940. Louis Zamperini, the American distance runner, competed in the 1936 Olympics, and later became the subject of the bestselling book Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand, published in 2010, and a 2014 movie of the same title. Italian Americans continued their significant involvement in the labor movement during this period. Well known labor organizers included Carlo Tresca, Luigi Antonini, James Petrillo, and Angela Bambace. Italian American businessmen specialized in growing and selling fresh fruits and vegetables, which were cultivated on small tracts of land in the suburban parts of many cities. They cultivated the land and raised produce, which was trucked into the nearby cities and often sold directly to the consumer through farmer's markets. In California, the DiGiorgio Corporation was founded, which grew to become a national supplier of fresh produce in the United States. Italian Americans in California were leading growers of grapes, and producers of wine. Many well known wine brands, such as Mondavi, Carlo Rossi, Petri, Sebastiani, and Gallo emerged from these early enterprises. Italian American companies were major importers of Italian wines, processed foods, textiles, marble and manufactured goods. Second world war: Italian-American veterans of all wars memorial, Southbridge, Massachusetts, Frank Capra receiving the Distinguished Service Medal from General George C. Marshall, 1945. Enrico Fermi, architect of the nuclear age, was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on induced radioactivity. Dominic Salvatore Don Gentile on the wing of his P-51B, 'Shangri-La'. Also known as "Ace of Aces", he was a World War II USAAF pilot who surpassed Eddie Rickenbacker's World War I record of 26 downed aircraft. As a member of the Axis powers, Fascist Italy declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, four days after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. As a consequence, Executive Order 9066 called for the compulsory relocation of more than 10,000 Italian-Americans and restricted the movements of more than 600,000 Italian-Americans nationwide. They were targeted despite a lack of evidence that traitorous Italians were conducting spy or sabotage operations in the United States. Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts in September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. Political refugees from Mussolini's regime, they disagreed among themselves whether to ally with Communists and anarchists or to exclude them. The Mazzini Society joined together with other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1942. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members, Carlo Sforza, to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the fall of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy. Between 750,000 and 1.5 million people of Italian descent are thought to have served in the US armed forces during the war, about 10% of the total, and 14 Italian Americans received the Medal of Honor for their service. Among these was Sgt. John Basilone, one of the most decorated and famous servicemen in World War II, who was later featured in the HBO series The Pacific. Army Ranger Colonel Henry Mucci led one of the most successful rescue missions in U.S. history, that freed 511 survivors of the Bataan Death March from a Japanese prison camp in the Philippines, in 1945. In the air, Capt. Don Gentile became one of the war's leading aces, with 25 German planes destroyed. Film director, producer and writer Frank Capra made a series of wartime documentaries known as Why We Fight, for which he received the U.S. Distinguished Service Medal in 1945, and the Order of the British Empire Medal in 1962. Biagio (Max) Corvo, an agent of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.), drew up plans for the invasion of Sicily, and organized operations behind enemy lines in the Mediterranean region during World War II. He led the Italian Secret Intelligence branch of the O.S.S., which was able to smuggle hundreds of agents behind enemy lines, supply Italian partisan fighters, and maintain a liaison between Allied field commands and Italy's first post-Fascist Government. Corvo was awarded the Legion of Merit for his efforts during the war. The work of Enrico Fermi was crucial in developing the atom bomb. Fermi, a Nobel Prize laureate nuclear physicist, who immigrated to the United States from Italy in 1938, led a research team at the University of Chicago that achieved the world's first sustained nuclear chain reaction, which clearly demonstrated the feasibility of an atom bomb. Fermi later became a key member of the team at Los Alamos Laboratory that developed the first atom bomb. He was subsequently joined at Los Alamos by Emilio Segrè, one of his colleagues from Italy, who was also destined to receive the Nobel Prize in physics. Three United States World War II destroyers were named after Italian Americans: USS Basilone (DD-824) was named for Sgt. John Basilone; USS Damato (DD-871) was named for Corporal Anthony P. Damato, who was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for his valor during World War II; and USS Gherardi (DD-637) was named for Rear Admiral Bancroft Gherardi, who served during the Mexican–American and U.S. Civil Wars. World War II ended the mass unemployment and relief programs that characterized the 1930s, opening up new employment opportunities for large numbers of Italian Americans, who significantly contributed to the nation's war effort. Much of the Italian American population was concentrated in urban areas where the new war materiel plants were located. Many Italian American women took war jobs, such as Rose Bonavita, who was recognized by President Roosevelt with a personal letter commending her for her performance as an aircraft riveter. She, together with a number of other women workers, provided the basis of the name, "Rosie the Riveter", which came to symbolize the millions of American women workers in the war industries.[Chef Boyardee, the company founded by Ettore Boiardi, was one of the largest suppliers of rations for U.S. and allied forces during World War II. For his contribution to the war effort, Boiardi was awarded a gold star order of excellence from the United States War Department. Wartime violation of Italian-American civil liberties: Internment of Italian Americans: From the onset of the (second world) war, and particularly following Pearl Harbor attack, Italian Americans were increasingly placed under suspicion. Groups such as The Los Angeles Council of California Women's Clubs petitioned General DeWitt to place all enemy aliens in concentration camps immediately, and the Young Democratic Club of Los Angeles went a step further, demanding the removal of American-born Italians and Germans—U.S. citizens—from the Pacific Coast. These calls along with substantial political pressure from congress resulted in President Franklin D. Roosevelt issuing Executive Order No. 9066, as well as the Department of Justice classifying unnaturalized Italian Americans as "enemy aliens" under the Alien and Sedition Act. Thousands of Italians were arrested, and hundreds of Italians were interned in military camps, some for up to 2 years. As many as 600,000 others were required to carry identity cards identifying them as "resident alien". Thousands more on the West Coast were required to move inland, often losing their homes and businesses in the process. A number of Italian-language newspapers were forced to close. Two books, Una Storia Segreta by Lawrence Di Stasi and Uncivil Liberties by Stephen Fox; and a movie, Prisoners Among Us, document these World War II developments. On November 7, 2000 Bill Clinton signed the Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act. This act ordered a comprehensive review by the Attorney General of the United States of the treatment of Italian Americans during the Second World War. The findings concluded that: 1.) The freedom of more than 600,000 Italian-born immigrants in the United States and their families was restricted during World War II by Government measures that branded them ‘enemy aliens’ and included carrying identification cards, travel restrictions, and seizure of personal property. 2.) During World War II more than 10,000 Italian Americans living on the West Coast were forced to leave their homes and prohibited from entering coastal zones. More than 50,000 were subjected to curfews. 3.) During World War II thousands of Italian-American immigrants were arrested, and hundreds were interned in military camps. 4.) Hundreds of thousands of Italian Americans performed exemplary service and thousands sacrificed their lives in defense of the United States. 5.) At the time, Italians were the largest foreign-born group in the United States, and today are the fifth largest immigrant group in the United States, numbering approximately 15 million. 6.) The impact of the wartime experience was devastating to Italian-American communities in the United States, and its effects are still being felt. 7.) A deliberate policy kept these measures from the public during the war. Even 50 years later much information is still classified, the full story remains unknown to the public, and it has never been acknowledged in any official capacity by the U.S. Government. In 2010, California officially issued an apology to the Italian Americans whose civil liberties were violated. The "2'ND wave of discrimination" endured by Italian Americans. #ITAA is leading efforts and exposing truth.

1945-1970 / Explosion Of Business, Sports, Entertainment And Civic Leadership

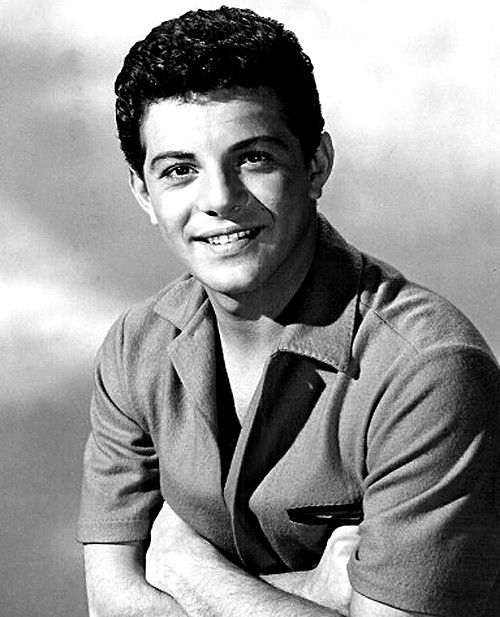

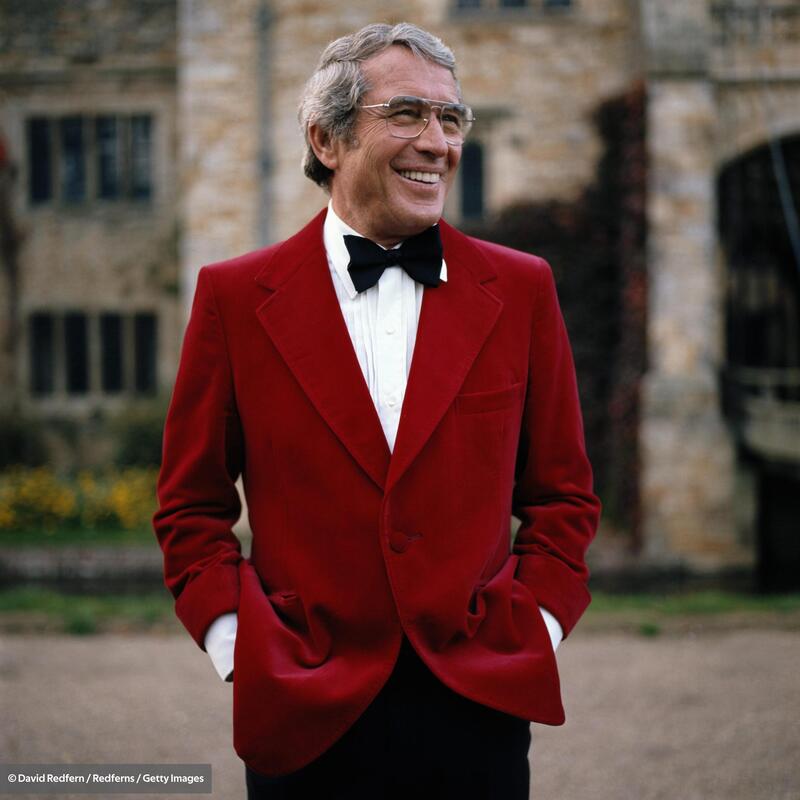

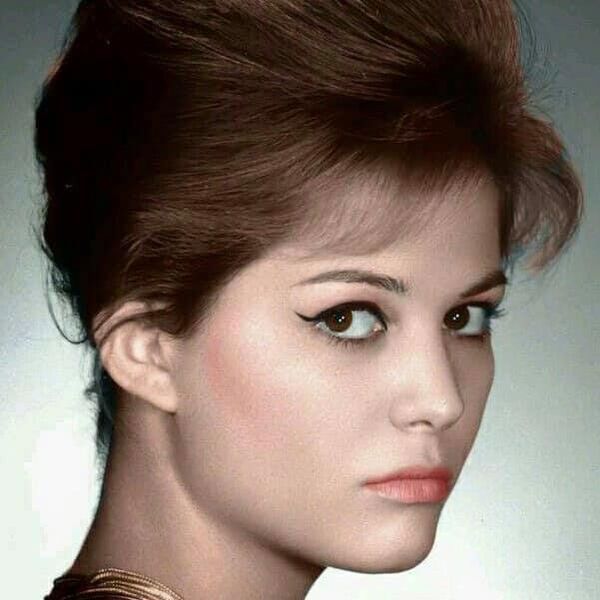

Post-World War II Period: Joe DiMaggio, considered one of the greatest baseball players of all time, in 1951. Italians continued to immigrate to the United States, and an estimated 600,000 arrived in the decades following the war. Many of the new arrivals had professional training, or were skilled in various trades. The post-war period was a time of great social change for Italian Americans. Many aspired to a college education, which became possible for returning veterans through the GI Bill. With better job opportunities and better educated, Italian Americans entered mainstream American life in great numbers. The Italian enclaves were sometimes abandoned by members of the younger generation who chose to live in other urban areas and in the suburbs. Many married outside of their ethnic group, most frequently with other ethnic Catholics, but increasingly also with those of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds. According to Dr. Richard D. Alba, director of the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the State University of New York at Albany, 8 percent of Americans of Italian descent born before 1920 had mixed ancestry, but 70 percent of them born after 1970 were the children of intermarriage. In 1985 among Americans of Italian descent under the age of 30, 72 percent of men and 64 percent of women married someone with no Italian background. Italian Americans took advantage of the new opportunities that generally became available to all in the post-war decades. Mario Cuomo, first New York Governor to identify with the Italian community. In the 1930s, Italian Americans voted heavily Democratic. Carmine DeSapio in the late 1940s became the first to break the Irish Catholic hold on Tammany Hall since the 1870s. By 1951 more than twice as many Italian American legislators as in 1936 served in the six states with the most Italian Americans. Anthony Celebrezze served for five two-year terms as mayor of Cleveland, from 1953 to 1962 and, in 1962, President John Kennedy appointed him as United States Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services). U.S. Senators included: John Pastore of Rhode Island was the first Italian American elected to the Senate in 1950. Scores of Italian Americans became well known singers including: Frank Sinatra, Mario Lanza, Perry Como, Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, Frankie Laine, Bobby Darin, Julius La Rosa and Connie Francis. Italian Americans who hosted popular musical/variety TV shows in the post-war decades included: Perry Como (1949 to 1967), piano virtuoso Liberace (1952–1956), Jimmy Durante (1954–1956), Frank Sinatra (1957–1958) and Dean Martin (1965–1974). Broadway, musical stars included: Rose Marie, Carol Lawrence, Anna Maria Alberghetti, Sergio Franchi, Patti LuPone, Ezio Pinza and Liza Minnelli. In music composition, Henry Mancini and Bill Conti received numerous Academy Awards for their songs and film scores. Classical and operatic composers John Corigliano, Norman Dello Joio, David Del Tredici, Paul Creston, Dominick Argento, Gian Carlo Menotti and Donald Martino were honored with Pulitzer Prizes and Grammy Awards. Movie director Frank Capra was a major force as pioneer movie creator. Wally Schirra one of the earliest NASA astronauts to enter into space (1962), taking part in the Mercury Seven program and later Gemini and Apollo programs. In professional football, Vince Lombardi set the standard of excellence for all coaches to follow. In college football, Joe Paterno became one of the most successful coaches ever (1966-2011). Four Italian American players won the Heisman Trophy before 1970: Angelo Bertelli of Notre Dame, Alan Ameche of Wisconsin, Gary Beban of UCLA, Joe Bellino of Navy. In college basketball, a number of Italian Americans became well known coaches in the post-war decades, including: John Calipari, Lou Carnesecca, Rollie Massimino, Rick Pitino, Jim Valvano, Dick Vitale, Tom Izzo, Mike Fratello, Ben Carnevale and Geno Auriemma. Italian Americans became nationally known in other diverse sports. Rocky Marciano was the undefeated heavyweight boxing champion from 1952 to 1956; Willie Mosconi was a 15-time World Billiard champion; Eddie Arcaro was a 5-time Kentucky Derby winner; Ken Venturi won both the British and U.S. Open golf championships in 1956; Donna Caponi won the U.S. Women's Open golf championships in 1969 and 1970. Italian Americans founded many successful enterprises during this period including: Tropicana Products, Zamboni, Subway, Mr. Coffee and Conair Corporation and 1,000's of smaller ones. Other enterprises founded by were Fairleigh Dickinson University, the Eternal Word Television Network and the Syracuse Nationals basketball team – later to become the Philadelphia 76ers. Robert Panara was a co-founder of the National Technical Institute for the Deaf and founder of the National Theater of the Deaf. Recognized as a pioneer in deaf culture studies in the United States, he was honored with a commemorative U.S. stamp in 2017. Seven Italian Americans became Nobel Prize laureates in the post-war decades: Mario Capecchi, Renato Dulbecco, Riccardo Giacconi, Salvatore Luria, Franco Modigliani, Rita Levi Montalcini and Emilio G. Segrè. Italian Americans continued to serve with distinction in the military, with four Medal of Honor recipients in the Korean War - and eleven in the Vietnam War alone, including Vincent Capodanno, a Catholic chaplain. #ITAA1970

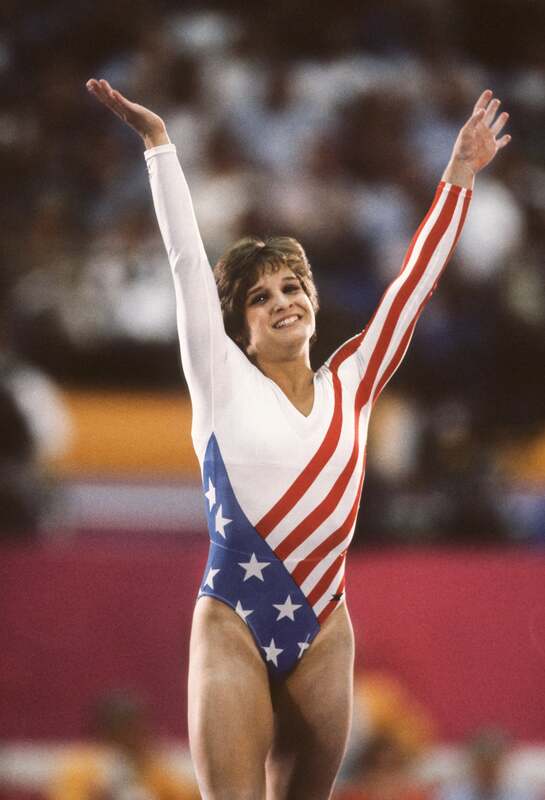

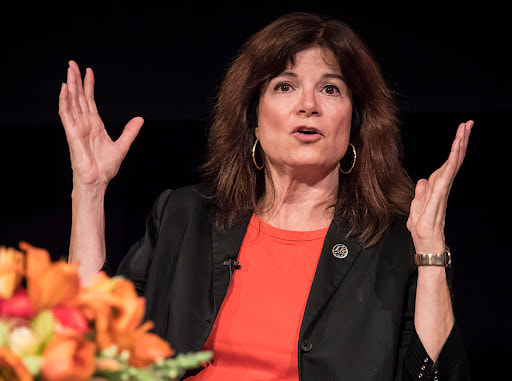

Special Historical Tribute To Women

Women: The contributions of Italian American women have been extraordinary. Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911. The victims were almost exclusively Jewish and Italian female immigrants. Italian women who arrived during the period of mass immigration had to adapt to new and unfamiliar social and economic conditions. Mothers, raising children and providing for the welfare of the family, demonstrated great courage and resourcefulness in meeting these obligations, often under adverse living conditions. Their cultural traditions, which placed the highest priority on the family, remained strong as Italian immigrant women adapted to these new circumstances. To assist the immigrants in the Little Italies, who were overwhelmingly Catholic, Pope Leo XIII dispatched a contingent of priests, nuns and brothers of the Missionaries of St. Charles Borromeo and other orders. Among these was Sister Francesca Cabrini, who founded dozens of schools, hospitals and orphanages. She was canonized as the first American saint in 1946. Married women typically avoided factory work and chose home-based economic activities such as dressmaking, taking in boarders, and operating small shops in their homes or neighborhoods. Italian neighborhoods also proved attractive to midwives, women who trained in Italy before coming to America. Many single women were employed in the garment industry as seamstresses, often in unsafe working environments. Many of the 146 who died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 were Italian-American women. Angela Bambace was an 18-year-old Italian American organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in New York who worked to secure better working conditions and shorter hours for women workers in the garment industry. The American scene in the 1920s featured a widespread expansion of women's roles, starting with the vote in 1920, and including new standards of education, employment and control of their own sexuality. "Flappers" raised the hemline and lowered the old restrictions in women's fashion. The Italian-American media disapproved. It demanded the holding of the line regarding traditional gender roles in which men controlled their families. Many traditional patriarchal values prevailed among Southern European male immigrants, although some practices like dowry were left behind in Europe. The community spokesmen were shocked at the notion of a woman marking her secret ballot. They ridiculed flappers and proclaimed that feminism was immoral. They idealized an old male model of Italian womanhood. Mussolini was popular with readers and subsidized some papers, so when he expanded the electorate to include some women voting at the local level, the Italian American editorials applauded him, arguing that the true Italian woman was, above all, a mother and a wife and, therefore, would be reliable as a voter on local matters but only in Italy. Feminist organizations in Italy were ignored, as the editors purposely associated emancipation with Americanism and transformed the debate over women's rights into a defense of the Italian-American community to set its own boundaries and rules. The ethnic papers featured a woman's page that updated readers on the latest fabrics, color combinations, and accessories including hats, shoes, handbags, and jewelry. Food was a major concern, and recipes were presented which adjusted to the availability of ingredients in the American market. Food supplies were limited in Italy by poverty and strict import controls, but abundant in America, so new recipes were needed to take advantage. In the second and third generations, opportunities expanded as women were gradually accepted in the workplace and as entrepreneurs. Women also had much better job opportunities because they had a high school or sometimes college education, and were willing to leave the Little Italies and commute to work. During World War II large numbers of Italian American women entered the workforce in factories providing war materiel, while others served as auxiliaries or nurses in the military services. Rosie the Riveter: Named after Rosie Bonavita from Long Island, N.Y., the image represented millions of American women who replaced male factory workers during World War II and helped get the country back on its feet. Miss Liberty, Peace Dollar: Modeled by Maria Teresa Cafarelli de Francisci from Clinton, M.A., the peace dollar was minted yearly from 1921 to 1928 and again in 1934 and 1935 as a commemorative of peace.After WW2, Italian American women acquired an increasing degree of freedom in choosing a career, and seeking higher levels of education. Consequently, the second half of the 20th century was a period in which Italian American women excelled in virtually all fields of endeavor. In politics, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman vice-presidential candidate, Ella Grasso was the first woman elected as a state governor and Nancy Pelosi was the first woman Speaker of the House. Mother Angelica (Rita Rizzo), a Franciscan nun, in 1980 founded the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN), a network viewed regularly by millions of Catholics. JoAnn Falletta was the first woman to become a permanent conductor of a major symphony orchestra (with both the Virginia Symphony Orchestra and the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra). Mary Lou Retton: Mary Lou Retton was the first female gymnast from outside Eastern Europe to win the Olympic gold medal in the women’s individual all-around competition at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, C.A. She was elected to the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in 1992. Penny Marshall (Masciarelli) was one of the first women directors in Hollywood. Catherine DeAngelis, M.D. was the first woman editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association. Patricia Fili-Krushel was the first woman president of ABC Television. Bonnie Tiburzi was the first woman pilot in commercial aviation history. Patricia Russo was the first woman to become CEO of Lucent Technologies. Karen Ignagni has, since 1993, been the CEO of American Health Insurance Plans, an umbrella organization representing all major HMO's in the country. Nicole Marie Passonno Stott was one of the first women to go into space as an astronaut. Carolyn Porco, a world recognized expert in planetary probes, is leader of the imaging science team for the Cassini probe, presently in orbit around Saturn. The National Organization of Italian American Women (NOIAW), founded in 1980, is an organization for women of Italian heritage committed to preserving Italian heritage, language and culture, promoting advancement of women of Italian ancestry. Exceptional!